McCartney and McCullin: the power of photography

2020 delivered many global challenges, but also the opportunity for reflection. Two major photography retrospectives in the city of Liverpool – Don McCullin at Tate Liverpool and Linda McCartney at the Walker Art Gallery – are such opportunities. Both are considered distinguished photographers of the 20th Century. Both started their careers in the 1960s and each travelled the world – McCullin in international war zones and McCartney on the road as part of the band Wings. When one thinks of McCullin’s moving and harrowing images of conflict and poverty, they wouldn’t naturally compare them with McCartney’s vibrant images of musicians or playful, humorous photos of her children. Yet the retrospectives enable a comparison of the two photographers and show the power of the photographic medium, how it can transcend across subjects, genres, people and places. Photographers can take images in the same city and in the same year, with very different results. Comparing McCartney and McCullin allows us to understand a photograph is never the whole story but an invitation to engage. We can scrutinise what the photographer themselves saw and what the presented scene can tell us about ourselves, society or even art.

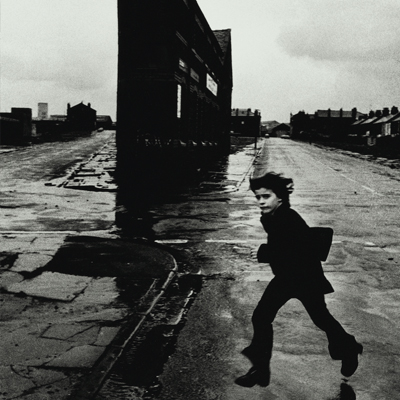

In both exhibitions one could argue McCullin and McCartney are presenting their version of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare, 1932, an image that defines his photography practice of the ‘Decisive Moment’ with a man leaping across a puddle in Paris. At Tate Liverpool we find a lone girl leaping through the photograph (image 1), a derelict Liverpool landscape in the background, her shadow reflected on the rain-soaked ground, like the shadow we see in Bresson’s image. The background of the McCullin image suggests this girl’s ‘playground’ is one of hardship, and somewhere we wouldn’t wish to see children. In McCartney’s image Paul, Stella and James, Scotland, 1982 (image 2) we find the decisive moment also captures a leap of faith – this time one of playful abandon. The derelict Liverpool landscape is replaced with the rolling Scottish hills and a watchful father, sister and dog. Her son James’s foot in the air is flat, as if he is walking. If McCartney had chosen to shoot a second before or after – the leap would be entirely different – James would not be walking in the air and the elements that make the photo so striking would be altered. We see how a photographer’s choice of when to shoot often makes the photograph.

Both photographers captured Liverpool in the seventies and eighties. McCullin’s Liverpool in the seventies (image 3) shows a woman passing McCullin by at a car boot sale, rollers in her hair, frowning, with a child holding each of her hands. The car boot sale is visible in the background and it is an image hard to date and hard to relate to the cosmopolitan city it is now. To the far right of the image is a pile of shoes, providing a thread to the Liverpool works of Linda McCartney that are on show at the Walker. Three Shoes, Liverpool, 1981(image 4) finds McCartney focussing closely on three different shoes facing each other on a pavement. There is no other context shown, only the surround of concrete slabs. How did the shoes come to be here? Are they the aftermath of too much fun the night before? From an overflowing bag? Car boot sale? It is these unanswered questions that make the image intriguing.

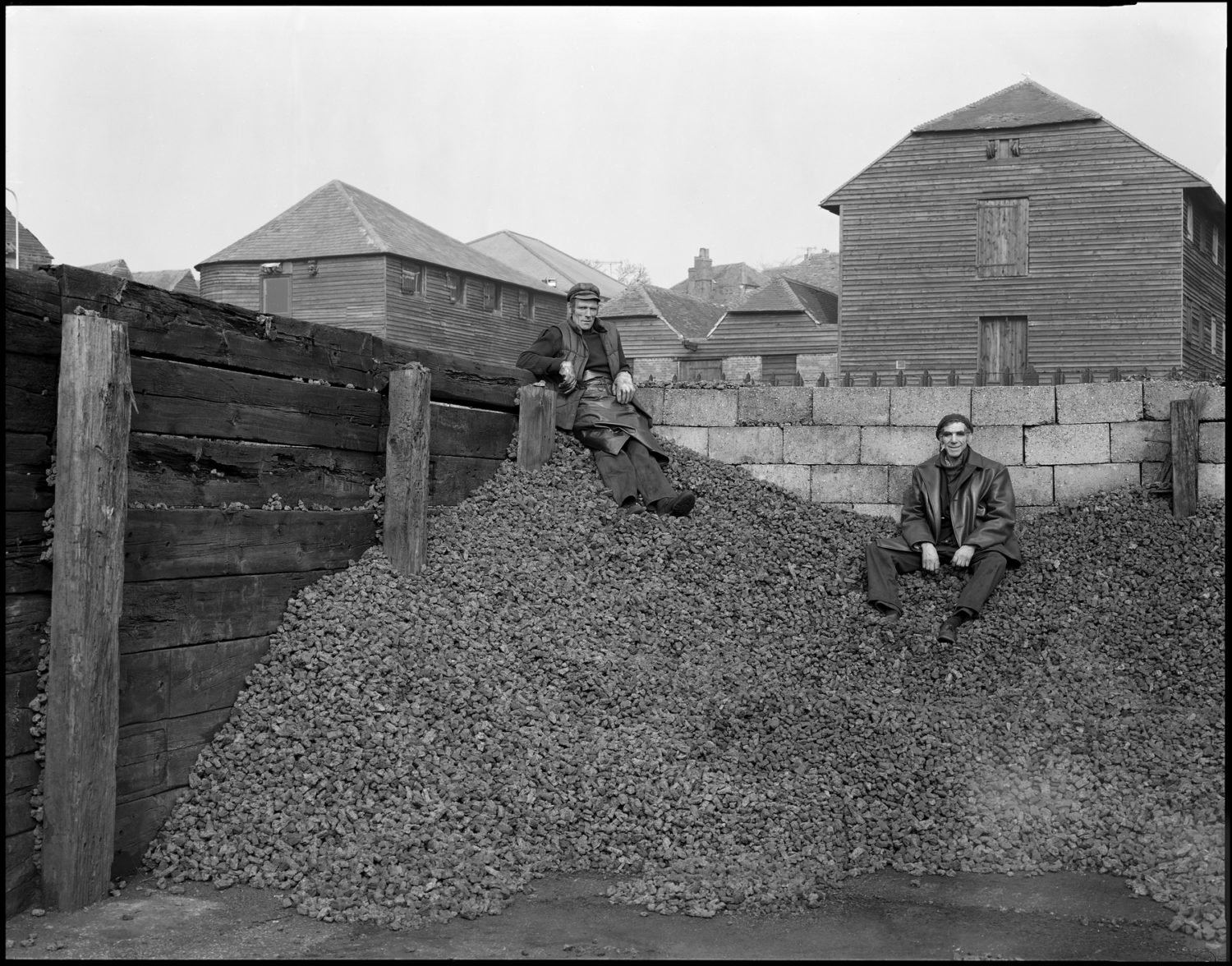

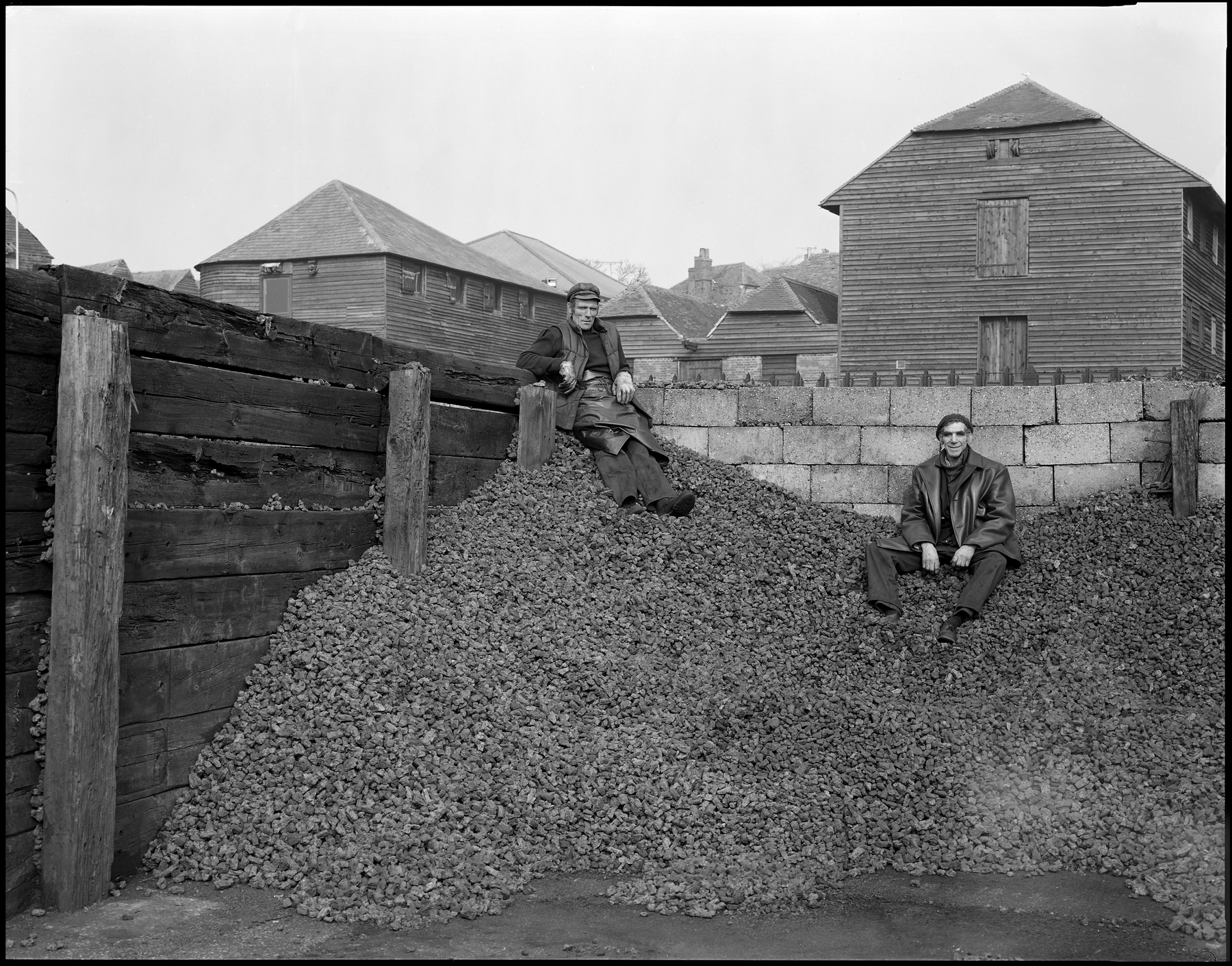

The miners’ strikes in Britain, which lasted up until 1985, made coal a politicised resource. Both McCullin and McCartney engaged with coal as a subject in their photography. McCartney’s Coalmen, Sussex, 1981 (image 5) captures two smiling men sitting on top of a coal heap with a wooden building behind, making the image look like it could have been taken much earlier in the century. The sitters of McCartney’s eye are comfortably returning her gaze while they seem to be taking a break from their laborious job. In McCullin’s Unemployed Men Gathering Coal, Sunderland 1972 (image 6), the viewer is faced with the repetition of the backs of a group of men scrambling over a pile a coal, so engrossed in their search that they are unaware of being photographed. There seems to be an urgency in their out stretched arms and hunched backs. Urgency is absent in McCartney’s still portrait. The titles of the images tell us employment, or the lack of it, has in some way brought the sitters to where they are. We see how the stability of employment can change a person’s demeaner and influence the outcome of a photograph. These are two of many images with similar subject matters but different evocations on view at each exhibition in Liverpool.

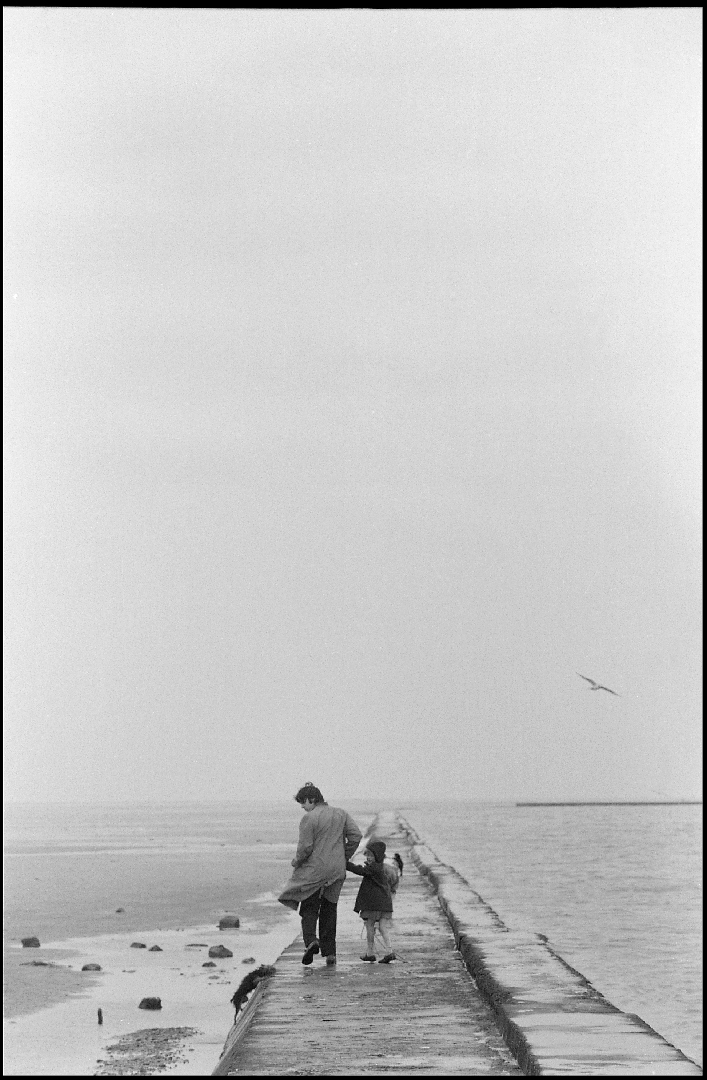

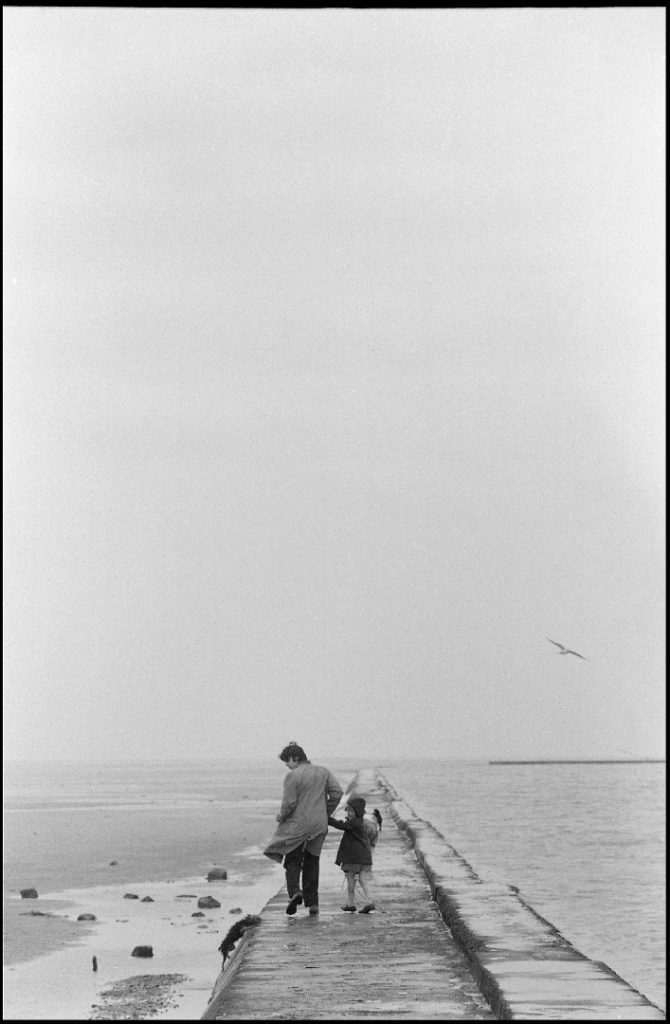

Another example of this, is McCartney’s and McCullin’s take on two figures walking along one Liverpudlian path: On the Pier, Wirral, 1968 (image 7) by McCartney and Liverpool 8 Neighbourhood, Liverpool circa 1970 (image 8) by McCullin. Two different images of an adult and child hand in hand, water each side of them. The water found in McCullin’s image are large puddles each side of the duo as they walk into the silhouette of terraced houses. Alternatively, McCartney’s father-daughter duo are surrounded by the sea, walking along the pier into infinity. Both photographers saw something in the pairs walking away from them with the sky above and water below. Both photographs show different paths each person takes in a city, as in life, and how varied it can be. Each makes us pause: a familiar scene yet something arresting in both.

Visiting both exhibitions, the McCartney Retrospective at the Walker and the McCullin exhibition at Tate Liverpool, gives the viewer a more rounded – fuller – view of humanity and of the human sensibility. Both exhibitions exemplify the power of the photographic medium to create memorable images and capture an essence of a person, a place and the photographer themselves. Visitors will leave each exhibition with differing emotions having gained an insight into different worlds. The exhibitions provide a moment of reflection – McCullin’s work reminding us to be socially conscious, to think outside of your immediate surroundings and engage with the community. Whereas McCartney’s approach to finding beauty, joy and humour in the everyday reminds us to be present, as we don’t know when it could all change: a sentiment experienced by all in 2020.