Linda McCartney and Colour Photography

In 1966 Linda McCartney had her first photography assignment printed in Town & Country magazine. In the space of three years she went on to be the house photographer for the Fillmore East, had her photographs feature throughout J Marks’ book Rock and Other Four Letter Words: Music of the Electric Generation, was voted US Female Photographer of the year in 1967 and was the first female photographer to have her work published on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. It is this trajectory, which includes the photographic work that Linda is best known for; yet in Mother and Child, Corfu, 1969, we have a glimpse of how her eye for the unusual and the unfamiliar, and her photographic empathy translated into her personal and documentary style photography.

Working and living in New York in the mid to late-sixties Linda found herself in the middle of a decade of innovative and energetic art, from the ubiquity of Pop art to the rise of conceptual and performance art. This climate of new and exciting endeavours in art extended to music, and Linda was, of course, privy to this. Arguably, being a first-hand witness to such a scene influenced Linda. She was not a formally trained photographer and after finishing studying for an Art History degree Linda took only two photography classes with Hazel Archer in Tuscon, Arizona, but was immediately captivated by it. Archer had studied at Black Mountain College under Josef Albers and Robert Motherwell and went on to teach many significant artists including Robert Rauschenburg. Linda cites Archer as inspiring her to become a photographer, with Archer showing Linda photographs “of life, of people, of sadness, of poverty, of nature, everything – I loved it”.[i] It is this passion and excitement for photography that comes to the fore in Mother and Child. Furthermore, Linda’s upbringing must have also lent to her artistic sensibility as her father was a lawyer to some of the art world’s greatest 20th Century painters including Willem de Kooning. It would seem that growing up in this context afforded Linda a nuanced appreciation of how to use colour and light to enrich photographs and how to look for atypical scenes, angles and juxtapositions; all elements which are transfused in her colour photographs.

Colour photography in 1969, the year Linda photographed Mother and Child, was not yet taken seriously within photographic circles, never mind the art world, and was instead associated with advertising and commercial use. Photography pioneers such as Alfred Steiglitz, Robert Frank and Walker Evans had all dabbled in colour photography but deemed black and white to be the true colours of photography, with Evans denouncing colour photography as corrupt and vulgar (although he later went on to only work in colour).[ii]The change in attitudes towards colour photography is usually credited to the 1976 exhibition of William Eggleston’s photographs at The Modern Museum of Art, New York (MoMA). Eggleston’s colour depiction of everyday life in the south of the United States was seen to use colour as a means of expression; the photographs would have lost their poignant, surrealist nature if shot in black and white. As Geoff Dyer describes the photographs, “the use of colour turned the banal into something extraordinary”.[iii] However, it was not just Eggleston working in colour with many renowned photographers working in colour prior to 1976 who have since been appreciated with hindsight. In fact, the press release for Eggleston’s 1976 exhibition acknowledged a new generation of young photographers working with colour in a manner that distinguished them from their forebears. MoMA described the work as demonstrating “a confident spirit of freedom and naturalness’”[iv]. Linda’s photographs prior to 1976 had both qualities. MoMA went on to claim the new emerging colour photography as:

… existential and descriptive; these pictures are not photographs of colour, any more than they are photographs of shapes, textures, objects, symbols, or events, but rather photographs of experience, as it has been ordered and clarified within the structures imposed by the camera.

In relation to Mother and Child the experience of the photographer is prominent, particularly as she chose to shoot in colour—something she often did when shooting on holiday or in nature (yet Linda, looking back on her photography, did admit she shot predominantly in black and white due to her early influences of black and white films and television).[i]The fact that Linda was not trained in photography and didn’t usually engage with the theorisation or critique of the practice makes it unlikely that the pronouncements of the photographic elite on colour photography impacted on her work. Instead it appears her lack of formal training encouraged her to use colour film and to follow her instinct:

As far as knowing when to shoot, I always relied totally on my instinct. I believed I could feel when there was a good picture.

The idea of ‘instinct’ and emotion in Linda’s work is paramount, and her ability to capture in an instant something striking and somewhat surreal is epitomised in Mother and Child.

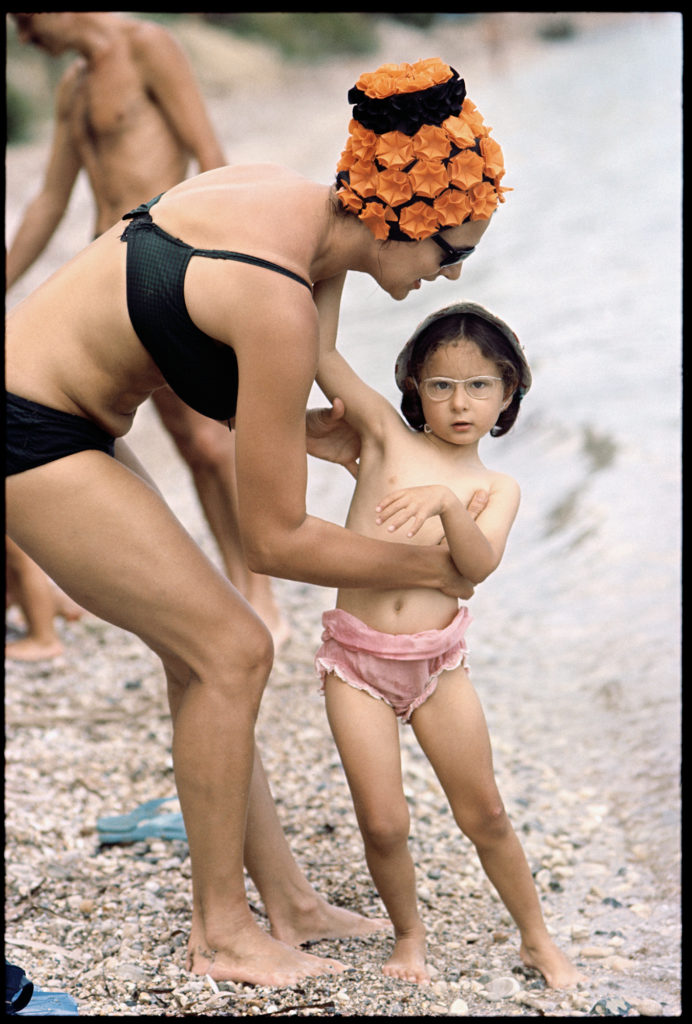

In Mother and Child, we have an orange three-dimensional hat. Pink frilly briefs, and a young girl’s spectacle-framed face all catching our eye. The nonchalant stance of the child, who returns the photographers gaze, sweeps our eye into the middle of the composition where we are instantly drawn by the textured orange hat to her mother. Without the use of colour film the surreal and comical impact of the brightly coloured textured hat on a beach, with people in their bathing suits would be lost. However, it is not the colour and texture of the orange hat or the flecks of turquoise blue we can see in the sand that make this photograph worth noting, it is the existential element of the photograph, the photographer’s experience that translates via the camera, that elevates Mother and Child from a holiday snapshot to an established photograph. Linda’s chosen composition—choosing to shoot the image at the precise moment before the child is lifted in the air—complements the idea of this being a ‘photograph of experience’. This is not only of the subject’s experience, but also perhaps Linda’s experience as a mother herself, and an experience of witnessing the scene, and also of the viewer witnessing this ‘pre-embrace’.

We often see the embrace of a mother and child in art, it has been depicted for hundreds of years; however, it is rarer to view the ‘pre-embrace’—the technicality of a mother picking up a child—the positioning and negotiating of the human form and human touch—such as it has been captured in Mother and Child. The mother has her feet firmly in the sand, her hands under the child’s underarm, her mouth open indicating speech—presumably a conversation with her daughter. The child leans in to her mother with her left foot already having left the ground, yet her stare is towards the viewer, at the camera, at Linda, and suggests her body is in autopilot, she knows how to be picked up and doesn’t have to think about it— her interest, her attention, is instead with the photographer. The returned gaze here is important: it establishes a photographic agency, as returning the photographer’s gaze creates a space for the subject (i.e. the child) in the photographic conversation and in the frame of the image. The power dynamics of the gaze is much discussed in the discourse around documentary photography, and here we have Linda, allowing her photographic gaze to be returned by the subject. This positions her into direct dialogue with the photographed person and gives the subject what can be described as ‘photographic agency’. Photographic agency is not necessarily applicable to all of Linda’s documentary-style work but here it is wrapped up with the existential nature of the image, surrealism and a compassion from the photographer for the subject. Linda managed to echo such elements throughout her oeuvre regardless if the subject was a stranger, friend, family member, animal or flower.

The real thing that makes a photographer is more than just a technical skill, more than turning on the radio. It has to do with the force of inner intention. I have always called this a visual signature.

Linda stated the above in an article entitled, “On the photographic instinct”, echoing qualities attributed to the colour photography arising out of the 1970s. Additionally, Linda’s visual signature came from trial and error, from her outlook onto the world, her compassion and empathy for people, animals and the environment. Her signature was the ability to evoke humour and wit in many of her photographs. Linda was a photographer who used the medium as a tool to analyse her surroundings and her outlook on life.

It must be noted that the photographer’s eye and visual signature goes beyond the action of taking the photograph and continues into the editing and printing process—it has to then look at the roll of photographs taken and decide which is the image they wish to share with the world. This reflects Henri Cartier Bresson’s argument in The Decisive Moment where he emphasises the choice involved in photography—from the scene the image was taken at to the printing process. Linda chose Mother and Child to feature in her Roadworks book published in 1996. Looking at the roll of photographs taken on the beach in Corfu one can see that Linda very much relied on her instinct as there are only four photographs of the mother and child together. Linda had to trust her instinct at the time to stop shooting. She had to trust she had the shot she wanted and trust she had captured the moment she was experiencing. Additionally, the choice of this particular frame over the three others demonstrates Linda had a strong sense of her visual signature and understood that in comparison to the other frames, the Mother and Child frame had more humour and an overtly ‘surreal’ element.

The idea of surrealism in photography goes beyond the original intentions of the surrealist movement and, as Susan Sontag argues, the act of photography, by duplicating the world, is surrealist in itself; the world in a photograph becomes “narrower but more dramatic than the one perceived by natural vision.” We can therefore consider that Linda understood the ‘dramatic’ quality of photography and in viewing her roll of photographs from Corfu she found the surreal and the dramatic were present in the ‘pre-embrace’ of the mother and child.

Linda uses the surrealist essence of photography to her advantage in John Lennon, London, 1969. John stands against a bright purple background, eyes downcast. He looks lost in thought standing at the edge of the frame of the image. The bright monotone of the background seems to hold John in a place, in a moment of time. The empty space in two thirds of the image lets the viewer explore the connection between the photographer and subject, without distraction from the background, particularly as the subject looks so unaware that the photograph is being taken in such close proximity. Evidently what Linda has achieved here is an isolation of the image from the reality in which it was taken. This is a characteristic of photography explored by the photographer Luigi Ghirri. Ghirri wrote in his essay ‘Cardboard Landscapes’(1973) that the photographs he took of everyday objects (objects which are often observed passively) became his ‘own’ when the photographs presented a different discourse; when a new meaning could be attached to them due to their isolation from the context they were taken in.[i] This idea is furthered in another of Ghirri’s essays where he states:

In photography, the deletion of the space that surrounds the framed image is as important as what is represented; it is thanks to this deletion that the image takes on meaning, becoming measurable. This image continues, of course, in the visible realm of the deleted space, inviting us to see the rest of reality that is not represented.

In Linda’s John Lennon, the photograph and its given title give the viewer pause to consider the intimate and serene moments latent in the middle of a performance. It is only by seeing the whole roll of film that the viewer understands the ‘deleted space’ was in-fact Lennon on stage, with a large guitar amplifier and George Harrison to his left, during The Beatles’ Let It Be sessions at Twickenham. Linda saw that for her photograph she did not need to include the band members, instruments or stage that everyone so readily associated with Lennon and The Beatles; that enough emotion, feeling and the artistic sensibilities of both the subject and the photographer could be portrayed in a tightly cropped, isolated composition; that Lennon had to be captured against the bright purple background, for the image would not otherwise have achieved what it has if captured in black and white film. Furthermore, Ghirri’s notion that deleted space has its own measurable meaning is even more significant when the viewer understands the deleted space is also the ending of The Beatles. The Let It Be sessions were some of the band’s last before dissolving. The image is then arguably less serene than we might originally have thought, with empty space to the left of Lennon having much more depth and emotion than at first sight. The dominant purple background is perhaps calling our attention to this isolation.

Linda’s early colour photographs complement those of her contemporaries, yet like many colour works by photographers, particularly female photographers, working in the 20th century the work is only now receiving the recognition it deserves. Recurring motifs in Linda’s work, such as humour, surrealism, empathy and social conscience, were often enhanced by her choosing of colour film to capture a subject.

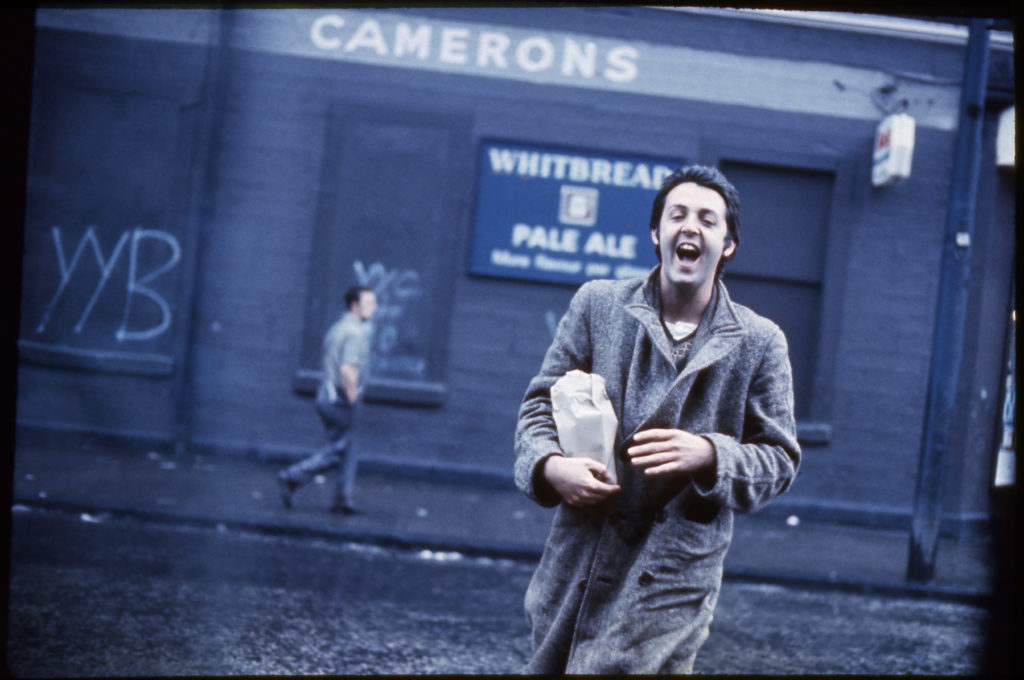

We see this in Paul, Scotland, 1970 another of her photographs saturated with one dominant colour—instead this time in blue.

The cold blue contrasts to the whole-hearted laugh of Paul and makes him stand out from the otherwise bleak background of the photograph. A discussion of colour might start with the aesthetic nature of the image, but it quickly becomes apparent that the photographer has chosen this medium to capture their subject in order to embrace the possibilities of colour photography. The photographer using photography to extend their ‘inner intention’ out into the world was something Linda believed and practiced, and she referred to it numerous times. Different interpretations of Mother and Child and John Lennon can co-exist but Linda’s attitude and visual signature will prevail:

I think you just feel instinctively, you got to just click on the moment. Not before it and not after it. I think if you are worried about light meters and all that stuff, you just miss it. For me it just came from my inners, as they say. Just excitement, I love it – I get very excited.